If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Principal Consultant Mark Turner asks: when is the right time to change?

We have all heard the phrase, ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’, used either jokingly to justify inactivity, or slightly more seriously as rationale when prioritising where effort is best invested.

I am not sure who made the initial statement, although views suggest that T. Bert Lance, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget in Jimmy Carter’s 1977 administration, promoted this mantra.

Apparently, Lance was convinced he could save the USA billions of dollars though the adoption of this simple motto. His view was, “That’s the trouble with government: fixing things that aren’t broken and not fixing things that are broken.”[i]

It is understandable to focus on what is causing you the most harm and seek to improve that as swiftly as possible. Fixing a burning platform or dramatically enhancing an underperforming function can potentially realise a high return on investment and should result in an enhanced service and less effort to deliver this in the future. Everybody wins.

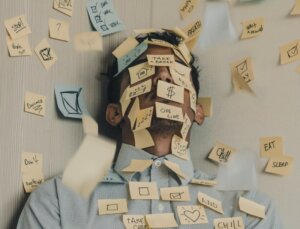

However, what if something is not broken but has deteriorated and is no longer performing at the optimum levels? How do you know? What would you do about it? Is it worth the additional investment to fix something which isn’t broken?

Outside of work, my hobby is playing tennis. I’ve owned the same racket for three years and since I don’t hit the ball very hard, I have yet to break a string.

Recently, a coach commented that you should change your racket strings the same number of times per year, as you play per week. He looked at my racket and said that while the strings were all intact, it was impeding my performance.

I took the plunge and invested £28 in a set of strings designed to suit my playing style. When the re-stringing was complete, I arranged a game with a friend with whom I play regularly.

It’s worth mentioning that my opponent is half my age, considerably faster and more powerful than me, and typically wins whenever we play. However, my service was now better, with the new strings providing more power and spin.

Although I lost the first set 7-5, I won the second 6-1. One small change – to something which wasn’t broken – resulted in tangible improvements to my performance, and with no extra effort on my part.

There are many other skills I need to develop to improve my game, but this experience made me wonder about the work environment. How often are we so focused on fixing the big issues that we miss simple opportunities to improve?

Ultimately the mantra promoted by T.Bert Lance is valid because fixing a burning platform is going to be essential to recovery. However, how many big issues might be prevented from even arising if we could consistently identify performance deteriorations, and take positive action to get them back on track?

[i] http://www.phrases.org.uk